Racial Identity Development

Am I white or am I Black?

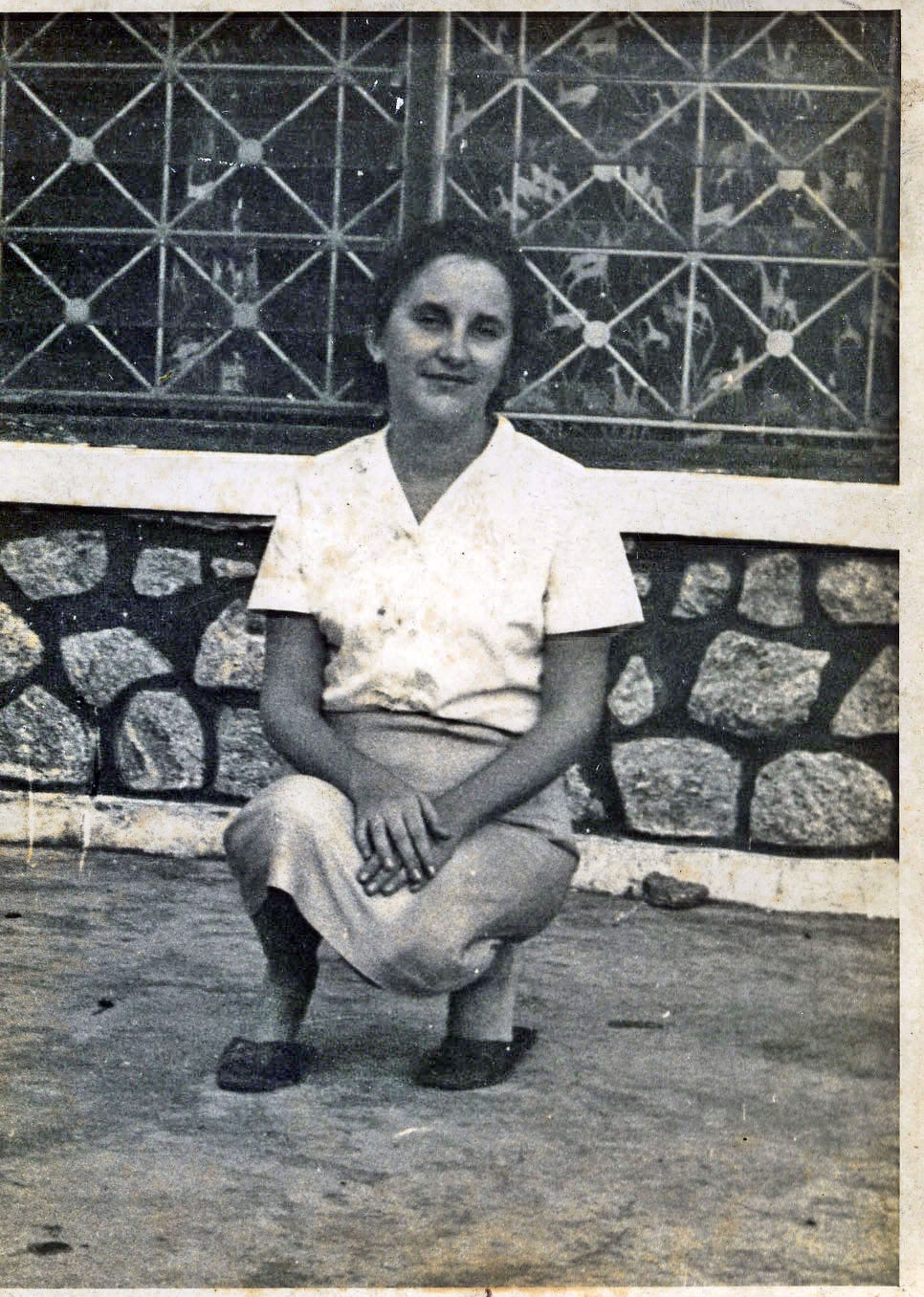

Today, I share with you a story about how my parents shaped my racial identity. It shows how your context matters as far as your racial identity development goes. I write this in honor of my mother. Today would have been her 90th birthday. I miss her a lot.

Growing up in Nigeria, culture and not race determined your heritage. I was confused as to where I neatly fit in. I have come to discover that there is such a thing as “racial identity development” where schemas give us broad outlines of the development of one’s racial identity. We will talk more on the podcast this week.

I imagine it was in the kitchen on a Sunday morning. It must have been. And, it must also have been a rainy day. That was when I usually had my daddy all to myself. I could only have been 8 or 9 years old. My sister had left home and was in college in America and my brother in boarding school. Feeling like an only child, I looked forward to any time with daddy, especially if he was in a good mood. Mummy was probably having her coffee in the study, patiently waiting on her husband to finish preparing the meal.

Sunday mornings were both weird and special in my home. In our highly pluralistically religious society, families either went to the mosque on Fridays or to church on Sunday mornings. Instead, my family's sabbath ritual was to go swimming at one of the pools at a four-star hotel that was open to the public. My mother was agnostic, the child of a somewhat absent Jewish father and a celebrated Irish American rebel family. My father was a sworn atheist and would not even enter the building of any religion. On Sundays, if it was raining, we did not go swimming. Instead, Daddy would treat us to one of his extravagant breakfasts.

This Sunday, Daddy and I were in the kitchen for a luxurious breakfast of yams and omelet with fruit and bacon on the side. In season, fresh squeezed homemade orange squash was the accompanying drink. I was his sous chef. I may not remember all the details clearly, but I do remember the conversation as if it happened yesterday.

Still stung by the events of the previous week, I wanted to ask my dad a burning question. A boy at school called me two derogatory skin color related names and I was livid and hurt.

I silently stared at Daddy's ebony-colored hand against the lightness of the wooden chopping board. His finger, against the silver sheen of the top of the blade, the even darker black of the handle, the green peppers, the white onions, and the red tomatoes were a riot of colors accompanied by the rhythmic slicing sound of the knife. His black skin was beautiful. I felt so inadequate and was aware of a seeping wound in my heart in the presence of pure black skin. The onions were stinging my eyes and as I started tearing up, I moved away to reduce the burn to my eyes. The aroma of bacon filled the kitchen, inviting the eggs to accompany the meal. I decided that it was time to risk asking one of my inane questions. My confusion and anxiety swirled among this burst of sensory overload, and my voice punctuated the harmonious silence as I tentatively said:

"Daddy?"

"Yes, baby pie?"

"What am I?" He stopped and looked at me quizzically and turned back to chopping for the omelet.

"Ah, huh, Ki Lo De, what are you talking about?" he said in Yoruba - what is wrong? As a very talkative child, I was pretty famous for coming up with annoying questions out of left field and he probably thought I was going down a rabbit hole known only to me. Again.

"I don't understand. Am I black, or is it .... white?" I blurted out. It must have been the tinge of sadness in my voice or the way the word "white" stuck in my throat, or maybe it was the profound exhaustion that seeped out of me as I said these words, he stopped chopping, knife still in his hand, and turned to me.

He furrowed his brow and gravely said, "Baby pie, you come from two worlds. Both have good, and both have bad. One is not better than the other. You choose the best of each world and make it your own. Leave the bad behind. You get to choose." His voice took on a stern tone as he punctuated the air between us with the knife, now his teaching tool. He was a professor and chalk his usual accompaniment, but today, it was a knife.

I took a couple of steps backwards with a look of consternation on my face, and he put the knife down probably realizing that he came across threateningly with the knife staring me in the face.

"What is going on?" he asked, his anger turning into soft concern.

"I don't like when people call me 'oyinbo.' I don't want to be called that. And I don't l like 'half-caste' either. And then sometimes they will say, 'mulatto.' I feel like when people see me, they just always want to point out that I am different. Yet I am not like mummy. She is white. And then sometimes, people do call me white. But I am not white."

He sighed, resuming breakfast preparation, “You are who you are. Your skin will never change. Who said you have to fit in perfectly into any box? Do not be ashamed of who you are. It does not make you better or worse than anyone that your mother is white. And yes, not everyone will like you. That is just life. The most important thing is that you get your education. That is what will open doors for you in life. If you study hard and work hard, you will be able to make a good life for yourself. It does not matter that you are girl. You can do anything a boy can do."

Today, I wonder why I never asked my mother these types of questions. Later in life, I did ask her but at that time, never.

The word, "oyinbo" is a colloquialism in Yoruba that, translated, means, "one whose skin has peeled." In a sea of very dark skinned people in Lagos, Nigeria in the 1970's, it was used to described white people or light skinned brown people such as fair skinned folks like me as we stood out like sore thumbs. It is considered a somewhat derogatory word as it is a word which creates "the other." Although it is often said mockingly, there is also a certain respect bred from colonialism that flavors the utterance of the word. In addition, lighter skin women are fetishized and therefore, it was unfortunately sometimes said with a sexual innuendo even to a child like me.

I was familiar with the fact that my lighter skin stood out in this world called "home." Often someone would hurl "oyinbo" at me as I walked or played and, to level the playing field, I would respond with "Mi kin sho 'yinbo" meaning, "I am not an 'oyinbo.'" And they would recoil with surprise that I spoke the language with such masterful inflection. After all, which oyinbo can speak Yoruba fluently? That is how I found myself continuously negotiating to rope in the seemingly far-away-box that others automatically put me into. It felt distant. It felt like I was on the edge of an island about to fall off. My place was a margin and I fought it ferociously.

Nigerians identify based on ethnic groups or tribes. We can look at the face of a person and guesstimate which tribe or part of the country they are from based on facial appearance or tribal marks. We describe ourselves as Yoruba, Hausa, Igbo, Efik, Ibbibio, Fulani, or Kanuri - the names of the tribes to which we belong. Or we would describe ourselves from the city we are from. Therefore, the descriptor 'oyinbo' meant you were not part of the over 250 ethnic tribes or over 500 languages spoken in the country. You were "other." You were foreign and not of this culture and place. You were most likely an expatriate. And you were probably naive and to be fooled.

The other derogatory colloquialism, "half-caste" was used to described mixed race children like me. A left over from the colonial days, throughout the British Empire this term was used to classify the "natives" based on their mixed-race heritage with white people. The "half-castes" were considered less barbaric because they had white blood and were accorded more power and more privileges because somehow, they were "superior" to the indigenous people. My opinion was and still is, I am not half a person, I am a whole person. Therefore, treat me like one and respect me as such. No half business here!

This colonial ideology did not come up in my home, but it permeated the larger society. My parents treated each other as intellectual peers, loved each other passionately, and argued about philosophical difference with vehemence born out of reading entirely too many books. The only time race came up in our home was when my parents reminisced about living in New York City and being denied living accommodations based on race.

Dear Reader,

What resonated with you? What made you come alive? When did you begin to become aware of your racial identity? Leave a comment and let me know. Thanks.